1 - Write a sentence for each. Words w asterisks do not require a sentence.

unscrupulous: adjective; having or showing no moral principles; not honest or fair.

indelible:

adjective;

that cannot be removed, washed away, or erased

encumbered:

verb; restrict or burden (someone or something) in such a way that free action or movement is difficult.

etiolating: to make pale; to deprive of natural vigor, make feeble

intrepid

megalomania: noun; a psychopathological condition characterized by delusional fantasies of wealth, power, or omnipotence.

in posse*: in potential but not in actuality.

in esse*: actually existing

cohere: verb; be united; form a whole.

remuneration: noun; money paid for work or a service

locution: noun; a word or phrase, esp. with regard to style or idiom.

arbiter: noun; one chosen or appointed to judge or decide a disputed issue; an arbitrator.

ambivalence: noun; the state of having mixed feelings or contradictory ideas about something or someone.

venery*: sexual indulgence

peripatetic: adj; traveling from place to place, esp. working or based in various places for relatively short periods.

consanguinity: noun;

a close relation or connection

bemuse: verb; puzzle, confuse, or bewilder (someone).

at par: at the original price; neither at a discount nor at a premium; - used especially of financial instruments, such as bonds.

platonic*: adj;

of, relating to, or being a relationship marked by the absence of romance or sex

parricide*:

the act of murdering one's father (patricide), mother (matricide) or

other close relative, but usually not children (infanticide).

the act of murdering a person (such as the ruler of one's country) who stands in a relationship resembling that of a father

a person who commits such an act

mortify: verb; to cause to experience shame, humiliation, or wounded pride; humiliate.

apostate: noun; a person who renounces a religious or political belief or principle

vex; verb; make (someone) feel annoyed, frustrated, or worried, esp. with trivial matters.

dexterity: noun; skill in performing tasks, esp. with the hands.

amoral: adj; lacking a moral sense; unconcerned with the rightness or wrongness of something.

concomitant: adj;

existing or occurring with something else, often in a lesser way; accompanying; concurrent:

an event and its concomitant circumstances.

votary: noun; a person, such as a monk or nun, who has made vows of dedication to religious service.

mendacity: noun; untruthfulness

phalanx*: noun;

a body of heavily armed infantry in ancient Greece formed in close deep ranks and files; broadly : a body of troops in close array

usurp: verb; to take and keep (something, such as power) in a forceful or violent way and especially without the right to do so.

approbation: noun; praise or approval

machination: noun; crafty scheme or cunning design for the accomplishment of a sinister end.

pseudonym: noun; candor a name that someone (such as a writer) uses instead of his or her real name.

epitaph: noun;

something written or said in memory of a dead person; especially : words written on a gravestone.

candor: noun; the quality of being open and honest in expression; frankness.

obstinate: adj; stubbornly refusing to change one's opinion or chosen course of action, despite attempts to persuade one to do so.

ardent: adj; enthusiastic or passionate

nimbus*: noun; b a radiant light that appears usually in the form of a circle or halo

about or over the head in the representation of a god, demigod, saint,

or sacred person such as a king or an emperor.

adroit: noun; clever or skillful in using the hands or mind.

cherub: noun; a type of angel that is usually shown in art as a beautiful young child with small wings and a round face and body

pagan: noun;

one who has little or no religion and who delights in sensual pleasures and material goods : an irreligious or hedonistic person

belligerent: adj; hostile and aggressive

jingo: noun; one who vociferously supports one's country, especially one who supports a belligerent foreign policy; a chauvinistic patriot.

prescience: noun; the fact of knowing something before it takes place; foreknowledge.

antipathy: noun; a deep-seated feeling of dislike; aversion.

unilateral: adj: performed by or affecting only one person, group, or country

involved in a particular situation, without the agreement of another or

the others.

felicity: adj;

the quality or state of being happy; especially : great happiness

querulous: adj; complaining in a petulant or whining manner.

2) Read Vidal, chap 4, pgs 65-80, take notes:

Create a character chart for each:

- Jefferson

- Madison

- Hamilton

- Washington

- Adams

- Maclay

Remember to consider what the character thinks, says, does, believes, how he is see by others, how he is seen by Vidal.

When you are finished consider what you've read in this chapter that

will help support you during your essay. Write a one paragraph reflection.

3) Discuss the conflict between Adams and Hamilton as members of Washington's cabinet.

Discuss Adams's role as president of the Senate (use his speech to the Senate on page 69)

Discuss Hamilton's role in the new government. How does Vidal characterize this role?

Discuss the developing political factions as noticed by Adams.

Discuss Washington's first interaction with the Senate. How does it illustrate the concept of checks and balances?

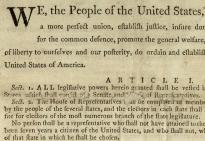

Detail from the Preamble of the US Constitution printed in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. (Gilder Lehrman Collection)

Detail from the Preamble of the US Constitution printed in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787. (Gilder Lehrman Collection)