Race and the American Constitution: A Struggle toward National Ideals

by James O. Horton

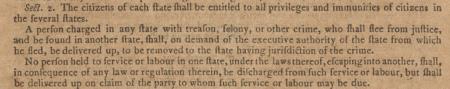

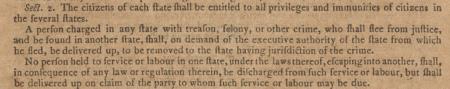

The fugitive slave clause in Article 4, Section 2 of the US Constitution. (Gilder Lehrman Collection)

The fugitive slave clause in Article 4, Section 2 of the US Constitution. (Gilder Lehrman Collection)

In the summer of 1852 Frederick Douglass took the platform at

Rochester, New York’s Corinthian Hall at the invitation of the Rochester

Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. The society had asked the former slave,

who had become one of the most recognized anti-slavery speakers in the

nation, to deliver an oration as a part of its Fourth of July

observance. Since the Fourth of July fell on a Sunday in 1852, the

society moved its observance to Monday, July 5, a decision with which

Douglass agreed. For years, free African Americans and many white

abolitionists had refused to celebrate the Fourth of July. Their refusal

was a protest against the nation’s continuance of slavery, even as its

Declaration of Independence professed its commitment to human freedom.

At New York City’s African Free School, for example, students vowed to

use the Fourth to attack the nation’s hypocrisy. In agreeing to address

the Rochester group on July 5, Douglass determined to use the occasion

for his own personal protest.

On July 5, 1852, a crowd of at least six hundred filled Corinthian

Hall as Douglass delivered one of the most striking lectures the

residents of Rochester or any other American city had ever heard. It

was, in fact, one of America’s most memorable orations, presented at a

critical moment in American history. Barely two years before, in 1850,

the federal government had issued an assault on the rights of African

Americans in the form of a harsh fugitive slave law. The law, part of a

massive compromise measure, was designed to appease the plantation

South, making it easier for slaveholders to recover fugitive slaves,

especially those seeking shelter in non-slaveholding states and

territories. Not only did the law mandate the capture and return of

fugitives, but it also endangered free blacks by requiring no legal

protections or defense for anyone charged with being a fugitive. The law

even prohibited accused fugitives from speaking in their own defense.

It also forced all citizens, when charged, to assist authorities and

slave catchers under penalty of fine and imprisonment for refusal. Such

injustice was a vivid reminder that African Americans could count on few

legal protections. Also, because this federal law nullified any

opposing state measure, it was a jarring reminder of the fact that the

law of the land protected the rights of slaveholders, virtually ignoring

African American rights.

As Douglass stood before the crowd, he asked the question that cut to

the core of America’s national contradiction. “What to the slave is

your Fourth of July?” His answer was even more unsettling to those

gathered to hear his words. It is, he said, “a day that reveals to him

[the slave], more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice

and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” In light of its public

commitment to human rights and personal liberty, America’s continued

support and protection of slavery, and its oppression of free African

Americans, Douglass leveled this indictment: “For revolting barbarity

and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.”

[1]

Douglass’s charge was stinging, but hardly unique within the African

American community or to any who had followed the history of race in

America to that time. From long before the United States claimed its

independence through revolution or established its governmental

structure based on its grand Constitution, the contradiction of a

freedom-loving people tolerating and profiting from depriving their

fellow human beings of freedom was central to any understanding of the

nation’s formation. Despite the lofty proclamations of the declaration

meant to justify the national break from England, and long before its

independence, America fell short of its ideals.

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, the representative

body appointed by the legislatures of the thirteen colonies then in

rebellion against Great Britain, ratified America’s Declaration of

Independence. This Congress had been meeting since the start of the

hostilities that came to be known as the American Revolution. In 1781,

after the American adoption of the Articles of Confederation, the

original governing instrument of the new nation, the Continental

Congress assumed the name the Congress of Confederation. This

representative body governed the nation through the uncertain years of

the Revolution until 1783. When Britain accepted the Treaty of Paris,

recognizing America’s independence and bringing the war to an end, the

United States of America struggled to maintain its national unity in the

face of competing state interests.

One of the most contentious issues of debate was the future of

America’s institution of slavery, which by the mid-1780s held hundreds

of thousands of Africans and African Americans in bondage. Some

Americans were struck by the obvious contradiction between America’s

egalitarian Declaration of Independence and its support of slavery.

During the Revolution and in its aftermath, many moved to abolish

slavery, especially in northern states where slaveholdings were

generally smaller and slaveholders less powerful than in the South. In

its constitution of 1777, Vermont became the first of the rebellious

colonies to banish slavery. In 1783 and 1784 Massachusetts and New

Hampshire followed, removing slavery through a variety of legal

interpretations of constitutional provisions. In 1780, Pennsylvania

passed legislation that provided for gradual emancipation, and four

years later Connecticut and Rhode Island did the same. Thus, by the time

the Constitutional Convention met in the spring of 1787, it was clear

to most delegates that the nation was moving toward a regional split on

the question of slavery.

The convention gathered at the State House in Philadelphia, the same

location where eleven years earlier the Declaration of Independence had

been signed. For four months, fifty-five delegates from twelve states

met to frame a Constitution for a new federal republic. Rhode Island,

fearing federal interference with its internal state affairs, refused to

send a delegate and was the only state not represented. Other states

had similar concerns about the power of centralized government, but sent

delegates nonetheless. In southern states, where slaves were most

numerous and the institution of slavery most economically and

politically powerful, regional leaders were determined to protect

slaveholding interests against federal interference. These fears were

heightened by the action of the Congress in July, just two months after

the convention convened. Then, still operating under the Articles of

Confederation, the Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, creating a

new territory from the land of the United States west of Pennsylvania

and northwest of the Ohio River. This was a vast region, more than

260,000 square miles encompassing the area of the modern states of Ohio,

Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and the northeastern part of

Minnesota. Included as part of the ordinance was a provision prohibiting

the movement of slavery into this Northwest Territory. Slavery

supporters interpreted this measure as an ominous sign for the future of

the institution.

Significantly, many of the largest slaveholders in the United States

were delegates at the Convention. Most of them were determined to guard

the institution against federal interference. The Georgia and South

Carolina delegations were adamant that their states would not accept any

national constitution that restricted slavery. “Without [slaves],”

argued Rawlins Lowndes of his home state of South Carolina, “this state

is one of the most contemptible in the Union.” It was the source of the

state’s “wealth, [and] our only natural resource,” he declared. South

Carolina, he believed was endangered by, “our kind friends in the

[N]orth [who were] determined soon to tie up our hands, and drain us of

what we had.”

[2]

Debate grew so heated that delegates sought to sidestep the issue of

slavery whenever possible, but they could not avoid the subject. The

Constitution, as accepted in the fall of 1787, protected slavery and

empowered slaveholders in important ways. In the three-fifths clause, it

allowed states to count three-fifths of their slave population in

calculating the population number to be considered for apportioning

representation in the US House of Representatives and the Electoral

College. Under this measure a single slaveholder with one hundred slaves

counted as the equivalent of sixty-one free people, giving the slave

states increased numbers of representatives and greatly expanding their

power in the US Congress. This was a compromise between delegates from

non-slave states who argued that slaves should not be counted at all in

determining population size for the purpose of congressional

representation and slave state delegates who demanded that the entire

slave population be added to state population figures. Thus, the

three-fifths compromise increased southern political power, allowing for

greater protection of the institution of slavery. The South’s

disproportionate power in the Electoral College allowed Thomas Jefferson

to secure the presidency in 1800.

The framers also wrote into the Constitution a provision that

assisted slaveholders in the recovery of fugitive slaves, especially

those who might seek sanctuary in non-slave states and territories. This

section read, “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under

the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any

Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour,

but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or

Labour may be due.”

[3]

This fugitive slave clause protected a slaveholder’s human property,

making the act of assisting a fugitive a constitutional offense. The

Constitution also protected slaveholders from their slaves, giving the

federal government the power to put down domestic rebellions, including

slave insurrections.

The third provision written into the Constitution concerning slavery

focused on the Atlantic slave trade. Debates over this issue were some

of the most contentious in the entire four months of the convention.

Although arguments on this issue broke largely along regional lines,

with the North favoring an end to American participation in the African

slave trade and the South standing against such a policy, restricting

the trade was a complex issue. Northern business often played a

significant role in financing the trade, outfitting and supplying the

crews, and building the ships that transported slaves to American ports.

This lucrative enterprise helped create northern support for protecting

the slave trade. Meanwhile, in some southern states concern about a

growing black population encouraged support for limiting slave

importation. During the Revolution and in its aftermath, Virginia

(1778), Maryland (1783), North Carolina (1786), and South Carolina

(1787) had actually closed their ports to the African slave trade,

hoping to limit the size of, and thus the danger posed by, their slave

populations. Indeed in an early draft of the Declaration, Jefferson had

included as one of the grievances giving rise to the quest for national

independence a paragraph condemning the slave trade and the whole

institution of slavery as a “cruel war against human nature itself”

forced on the colonies by Britain. Yet, the need for labor and the

increasing economic value of slavery overwhelmed these objections. It

was one thing for slaveholders to limit or expand the number of their

slaves, but most would never accept such a condemnation of slavery or

agree to give up control of the institution. In response to the

objections of his fellow slaveholders, Jefferson excluded that paragraph

from the final document.

The question of the extent of state power under the national

constitution was directly relevant to the question of slavery and the

slave trade. Some southern delegates insisted that the federal Congress

have no authority to interfere with slavery at all, but others agreed to

a middle ground. More moderate delegates supported a measure to deny

Congress any power to limit the slave trade for at least twenty years.

To many delegates, northern and southern, this seemed a practical

compromise. Nathaniel Gorham of Massachusetts rose to support the idea.

Some were uncomfortable with any constitutional reference to the trade,

but Virginia delegate James Madison raised the only voice against the

compromise. He had drafted a plan for a strong federal government, which

he called the Virginia Plan, and he argued that “Twenty years will

produce all the mischief that can be apprehended from liberty to import

slaves.” He then predicted that “So long a term will be more

dishonorable to the American character than to say nothing about it in

the constitution.”

[4]

Madison’s words did not persuade many of his fellow southerners who

demanded that the federal government should have no right to interfere

with the Atlantic slave trade. The compromise held, however. “The

migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now

existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the

Congress prior to the year 1808,” read the constitutional provision. It

also provided that “a tax or duty may be imposed on such importation,

not exceeding ten dollars for each person,” so long as the trade

remained legal.

[5]

Thus, in the three-fifths compromise, the fugitive slave clause, and

its twenty-year protection of the Atlantic slave trade, the Constitution

dealt with the slavery question, but never by name. So controversial

was the issue, that the framers consciously avoided the words “slave”

and “slavery” as they crafted the Constitution. Neither word appeared in

the document as accepted by the convention and submitted to the states.

As an article in the

Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer

announced, “the dark and ambiguous words . . . are evidently chosen to

conceal from Europe that, in this enlightened country, the practice of

slavery has its advocates among men in high stations.”

[6]

George Washington, one of the nation’s most revered leaders, attended

the convention as a Virginia delegate and remained largely silent

during these exchanges on slavery. He was a slaveholder but was also

ambivalent about slavery. His experience with black soldiers during the

Revolution had raised questions in his mind about the slave system, but

he did not argue against it. To end slavery immediately, he believed,

would be dangerous. He hoped for a gradual abolition of the institution,

but he understood the delicacy of the issue and its potential danger

for the formation of a strong national government. After the adoption of

the Constitution he explained that he was not happy with the

compromises needed to construct a document acceptable to the convention,

especially those on the slavery issue. In early January of 1788, he

wrote to Edmund Randolph, then governor of Virginia, “There are some

things in the new form [the Constitution] I will readily acknowledge,

which never did, and I am persuaded never will, obtain my

cordial approbation.”

[7]

Over the next half century, the Constitution was continuously used to

protect the institution of slavery from federal interference and

attacks leveled by the increasingly militant abolition movement. The

Constitutional standing of free African Americans was ambiguous,

however. Under its provisions the First US Congress passed a law in 1790

that specifically limited naturalized citizenship to white aliens.

Again, with constitutional sanction, the Second Congress passed

legislation establishing a “uniform militia throughout the United

States,” but limited it to “each and every free able-bodied white male

citizen of the respective states” between the ages of eighteen and

forty-five.

[8]

The Bill of Rights did not protect free blacks from local and state

laws that deprived them of virtually all those rights enumerated in the

first ten Constitutional amendments. Despite the 1787 ordinance that

outlawed slavery from the Northwest Territory, Congress provided that

only free white males could vote in the decision to carve out Indiana

from that region as a territory in preparation for statehood.

In the pre–Civil War years, the Constitution did not protect free

blacks from the racially discriminatory actions of individual states. By

1830, free blacks could vote on an equal basis with whites only in

Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania. In the

Northwest Territory, where slavery had been prohibited during the

post-Revolutionary era, territorial governments severely restricted the

rights of free blacks. Some required that African Americans post a bond

ranging from $500 to $1,000 in order to settle within the territory,

while others prohibited black immigration all together. Some of these

restrictions remained in force for much of the pre–Civil War period.

Illinois in 1848 and Indiana in 1851 incorporated the prohibition of

African American settlement into their respective state constitutions.

In 1849 the Oregon legislature prohibited African American settlement in

the territory. This restriction, paired with a ban on black voting

rights, was built into Oregon’s constitution as it was admitted to

statehood in 1859.

For many African Americans, a Constitution that would allow and even

support individual states that enslaved them and disregarded the liberty

of even those who were free was a pro-slavery document not to be

respected. William Wells Brown, a former slave who, like Douglass,

became an important figure in the abolition movement, was convinced that

as an instrument of proslavery power the Constitution must be replaced

by a new document oriented toward true liberty and human equality. “I

would have the [slaveholder’s] Constitution torn in shreds and scattered

to the four winds of heaven,” he announced. “Let us destroy the

Constitution and build on its ruins the temple of liberty.” Many white

abolitionists agreed that the Constitution was a product of pro-slavery

creation. In 1843 Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison proposed

that non-slaveholding states secede from the nation governed by any such

proslavery document as he held the Constitution to be. He called it “a

covenant with death and an agreement with Hell.” Eleven years later, on

the Fourth of July in 1854, Garrison publicly burned a copy of the US

Constitution, pronouncing it “the source and parent of the other

[American] atrocities.” As the document burned, he cried out: “So perish

all compromises with tyranny!” to which the abolitionist crowd replied

“Amen.”

[9]

Given the general denial of rights to all African Americans, free as

well as slave, and the growing impatience of abolitionists, white and

black alike, with the governmental support of racial injustice,

Douglass’s question to his fifth of July Rochester audience in 1852

might well have been, “What to freedom-loving Americans is the Fourth of

July?” Eventually, Douglass came to believe that the Constitution was

not a pro-slavery document, but that it was being subverted in its

intent by pro-slavery forces.

The Constitution, then, was a creation of the ideals, the interests,

and also the racial assumptions and prejudices of those who drafted it

and those who ratified it. The nation that took shape under its legal

sanctions both reflected and extended its original characteristics. As

the voices of anti-slavery grew louder and more strident during the

first half of the nineteenth century, the constitutional protections of

slavery came under increasing attack. Finally, the secession of the

southern states and the coming of civil war enabled President Abraham

Lincoln and his administration to remove constitutional protections for

slavery, and to prohibit it with the Thirteenth Amendment. In the

aftermath of the Civil War the Constitution was further reshaped to

remove race as a prohibition to citizenship. In 1857 the Supreme Court

had ruled that Dred Scott, a slave seeking his freedom, could not bring

his case before the federal court because African American people were

not and could not be American citizens. The Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution ratified in 1868 declared that citizenship could not be

withheld on account of race, and the Fifteenth Amendment ratified in

1870 sought to protect African American voting rights.

The post–Civil War amendments to the Constitution did not prevent

individual states, especially those in the South, from circumventing

constitutional protections for African American citizenship rights. They

did, however, provide a foundation upon which the twentieth-century

Civil Rights Movement could build. Despite the Supreme Court ruling in

the 1896

Plessey v. Ferguson case allowing the formation of the

Jim Crow segregation system, a series of court victories based on

constitutional civil rights protections led to the momentous 1954

Brown

decision and set the stage for the civil rights legislation of 1964 and

1965. American racial attitudes have traditionally contradicted

American professed ideals of freedom and equality. America’s

Constitution has reflected that contradiction and the struggle to

reconcile American rhetoric with American reality. Over the last two

centuries, freedom-loving Americans have remained determined to see

America live up to the Revolutionary values upon which it founded its

constitutional democracy.

[1] Frederick Douglass, “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro,” in Philip S. Foner, ed.,

The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass (New York: International Publishers Co., Inc., 1975), 181–204.

[2] Lawrence Goldstone,

Dark Bargain: Slavery, Profits and the Struggle for the Constitution (New York: Walker and Co., 2005), 3–4.

[3] United States Constitution, Article IV, Section 2.

[4] Quoted in Matthew T. Mellon,

Early American Views on Negro Slavery (New York: Bergman Publishers, 1969), 127–128.

[5] United States Constitution, Article 1, Section 9.

[6] Quoted in Hugh Thomas,

The Slave Trade (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997) 501.

[7] Jared Sparks, ed.,

The Writings of George Washington (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1855), 9:297.

[8] Quoted in John Hope Franklin and Genna Rae McNeil, eds.,

African Americans and the Living Constitution (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995), 23.

[9] Richard Newman, ed.,

African American Quotations (New York: Checkmark Books, 2000), 90; Goldstone, 16; Henry Mayer,

All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998), 445.

James O. Horton is the Benjamin

Banneker Professor Emeritus of American Studies and History, George

Washington University, and Historian Emeritus of the Smithsonian

Institution’s National Museum of American History. His books, coauthored

with Lois E. Horton, include In Hope of Liberty: Free Black Culture and Community in the North, 1700–1865

(1997) and Slavery and the Making of America

(2004), the companion book for the WNET PBS series of the same name that aired in February 2005.