The Antifederalists: The Other Founders of the American Constitutional Tradition?

The Great Debate

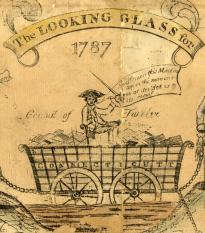

Detail

from the political cartoon “The Looking Glass for 1787,” which focuses

on the Federal/Antifederal conflict in Connecticut, shown here as a

wagon filled with debts and sunk in mud. (Library of Congress Prints and

Photographs Division)

Detail

from the political cartoon “The Looking Glass for 1787,” which focuses

on the Federal/Antifederal conflict in Connecticut, shown here as a

wagon filled with debts and sunk in mud. (Library of Congress Prints and

Photographs Division)The debate over the Constitution was not restricted to the pages of the nation’s papers. Arguments over the merits of the Constitution were conducted in taverns, town squares, and occasionally in the streets. Federalists and Antifederalists each made use of the rituals of popular politics, parading, and staging mock funerals and executions to express their views of the Constitution. In a few instances these spirited celebrations and protests escalated into full-scale riots. Violent outbursts, however, were the exception, not the norm, in the struggle over the Constitution.

Who Were the Antifederalists?

Antifederalists were never happy with their name. Indeed, Elbridge Gerry, a leading Antifederalist, reminded his fellow Congressmen that “those who were called antifederalists at the time complained that they had injustice done them by the title, because they were in favor of a Federal Government, and the others were in favor of a national one.” Since the issue before the American people was ratification of the Constitution, Gerry reasoned it would have been more appropriate to call to the two sides “rats” and “anti-rats!”[2]No group in American political history was more heterogeneous than Antifederalism. Even a cursory glance of the final vote on ratification demonstrates the incredible regional and geographical diversity of the Antifederalist coalition. Antifederalism was strong in northern and western New England, Rhode Island, the Hudson River Valley of New York, western Pennsylvania, the south side of Virginia, North Carolina and upcountry South Carolina. The opposition to the Constitution brought together rich planters in the South, “middle class” politicians in New York and Pennsylvania, and backcountry farmers from several different regions. Among leading Antifederalist voices one could count members of the nation’s political elite—aristocratic planters such as Virginia’s George Mason and the wealthy New England merchant Elbridge Gerry. Mason and Gerry were adherents of a traditional variant of republicanism, one that viewed the centralization of power as a dangerous step toward tyranny. The opposition to the Constitution in the mid-Atlantic, by contrast, included figures such as weaver-turned-politician William Findley and a former cobbler from Albany, Abraham Yates. These new politicians, drawn from more humble, middling ranks, were buoyed up by the rising tide of democratic sentiments unleashed by the American Revolution. These men feared that the Constitution threatened the democratic achievements of the Revolution, which could only survive if the individual states—the governments closest to the people—retained the bulk of power in the American system. Finally, Antifederalism also attracted adherents of a more radical plebeian view of democracy. For these plebeian populists, only the direct voice of the people as represented by the local jury, local militia, or the actions of the crowd taking to the streets, could fulfill their radical localist ideal of democracy. The democratic ethos championed by Findley and Yates proved far too tame for plebeian populists, such as William Petrikin, the fiery backcountry radical from Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

The Antifederalist Critique of the Constitution

Although there was considerable diversity among the opponents of the Constitution, the outline of a common critique of the Constitution slowly emerged as the document was debated in public. Three core issues defined this critique:1. The omission of a bill of rights

The absence of a bill of rights was an often-repeated criticism of the Constitution. Antifederalists not only believed that the inclusion of a bill of rights was essential to the preservation of liberty, but they also believed that a fundamental statement of political and legal principle would educate citizens about the ideals of republicanism and make them more effective guardians of their own liberty.2. The centralizing tendencies of the new government

The new powerful central government created by the Constitution would slowly absorb all power within its orbit and effectively reduce the states to insignificant players in a powerful new centralized nation state. Antifederalists feared that the new Constitution would create a central state similar to Great Britain’s fiscal/military model. The extensive powers to tax, the provision for a standing army, and the weakening of the state militias would allow this new powerful government to become tyrannical.3. The aristocratic character of the new government

The charge of aristocracy frequently voiced by Antifederalists could be framed in either democratic terms or in a more traditional republican idiom. Thus, for middling democrats or plebeian populists, the charge of aristocracy was in essence a democratic critique of the Constitution. According to this view, the Constitution favored the interests of the wealthy over those of common people. For elite Antifederalists, by contrast, the charge of aristocracy echoed the traditional republican concern that any government with too much power would inevitably become corrupt and would place the interests of those in power over the common good.

Antifederalism and the Historians

The changing historical view of Antifederalism has itself become a remarkable historical litmus test for the political mood of the nation. Throughout American history, Antifederalist ideas have been resurrected by groups eager to challenge the power of the central government. Historians have not been exempt from the tendency to see Antifederalism through a political lens. Over the course of the twentieth century historians continuously reinterpreted the meaning of Antifederalism. These different interpretations tell us as much about the hopes and fears of the different generations of scholars who wrote about the opposition to the Constitution as it does about the Antifederalists themselves.At the end of the nineteenth century, populists cast the Antifederalists as rural democrats who paved the way for Jeffersonian and Jacksonian democracy.[3] This interpretation was challenged by counter progressive historians writing during the Cold War era. For these scholars, the Antifederalists were examples of the paranoid style of American politics and were backward-looking thinkers who failed to grasp the theoretical brilliance of the new Constitution.[4] This claim was later challenged by Neo-Progressive historians who saw Antifederalism as a movement driven by agrarian localists who were opposed by a group of commercial cosmopolitan supporters of the Constitution.[5] The rise of the new social history during the turbulent era of the 1960s had relatively little impact on scholarship on Antifederalism. The many community studies produced by social historians were generally concerned with more long-term changes in American society and hence tended to shy away from the topic of ratification. Social history’s emphasis on recovering the history of the inarticulate also pulled historians away from the study of elite constitutional ideas in favor of other topics. [Thus, none of the many excellent New England town studies, for example, dealt directly with ratification. Some neo-conservative scholars actually faulted the new social history for abandoning constitutional politics entirely; see Gertrude Himmelfarb, The New History and the Old (1987)].

The Constitution was, however, of considerable interest to students of early American political ideology. For scholars working within this ideological paradigm, the struggle between Federalists and Antifederalists was a key battle in the evolution of American political culture. Some saw the opponents of the Constitution as champions of a traditional civic republican ideology, clinging to notions of virtue and railing at corruption. Others cast the Antifederalists as the forerunners of modern liberal individualism with its emphasis on rights and an interest-oriented theory of politics.[6]

Over the course of the twentieth century Antifederalism played a central role in a number of different narratives about America history. For some, opposition to the Constitution was part of the rise of democracy, for others, it heralded the decline of republicanism, while others saw it as source of modern liberal individualism. Given the heterogeneity of Antifederalism, it is possible to find evidence to support all of these claims, and more. Rather than seek a single monolithic true Antifederalist voice, it would be more accurate to simply recognize that Antifederalism was a complex political movement with various ideological strains, each of which made important contributions to the contours of early American political and constitutional life.

Antifederalism and the American Constitutional Tradition: The Enduring Legacy of the Other Founders

Historians and political scientists are hardly the only groups to show an interest in the ideas of the Antifederalists. Judges, lawyers, and legal scholars have increasingly canvassed the ideas of the Antifederalists in their effort to discover the original understanding of the Constitution and the various provisions of the Bill of Rights. Indeed, in a host of areas, from federalism to the Second Amendment, legal scholars and courts have increasingly turned to Antifederalist texts to support their conclusions.[7] If the past is any guide to the future, the ideas of the Antifederalists are likely to continue to play a prominent role in future constitutional controversies.

[1] Saul Cornell. The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (1999).

[2] Cornell, Other Founders.

[3] Orrin Grant Libby. The Geographical Distribution of the Vote of the Thirteen States on the Federal Constitution, 1787–88 (1894).

[2] Cornell, Other Founders.

[3] Orrin Grant Libby. The Geographical Distribution of the Vote of the Thirteen States on the Federal Constitution, 1787–88 (1894).

[4] Cecelia Kenyon. Men of Little Faith: The Anti-Federalists on the Nature of Representative Government (1955).

[5] Jackson Turner Main. The Antifederalists; Critics of the Constitution, 1781–1788 (1961).

[6] Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (1969); Lance Banning, The Jeffersonian Persuasion: The Evolution of a Party Ideology (1978); Richard Beeman, et al., eds. Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and National Identity (1987). For an early effort to frame the struggle over the Constitution in light of the perspective of new social history, see Edward Countryman, The American Revolution (1985; rev ed. 2003).

[7] Michael C. Dorf, “No Federalists Here: Anti-Federalism and Nationalism on the Rehnquist Court” 31 Rutgers Law Journal 741 (2000).

Saul Cornell is the Paul and Diane Guenther Chair in American History, Fordham University, and the author of The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (1999) and, with Jennifer Keene and Ed O’Donnell, American Visions: A History of the American Nation (2009).

[5] Jackson Turner Main. The Antifederalists; Critics of the Constitution, 1781–1788 (1961).

[6] Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (1969); Lance Banning, The Jeffersonian Persuasion: The Evolution of a Party Ideology (1978); Richard Beeman, et al., eds. Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and National Identity (1987). For an early effort to frame the struggle over the Constitution in light of the perspective of new social history, see Edward Countryman, The American Revolution (1985; rev ed. 2003).

[7] Michael C. Dorf, “No Federalists Here: Anti-Federalism and Nationalism on the Rehnquist Court” 31 Rutgers Law Journal 741 (2000).

Saul Cornell is the Paul and Diane Guenther Chair in American History, Fordham University, and the author of The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788–1828 (1999) and, with Jennifer Keene and Ed O’Donnell, American Visions: A History of the American Nation (2009).

No comments:

Post a Comment